A Short History of Steeple Claydon

The Middle Ages

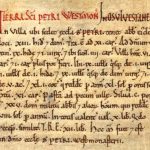

The earliest surviving document to mention Claydon by name is Domesday Book (1086).

A free translation of the Claydon entry follows:

‘ Alaric the cook holds Claindone from the King [William the Conqueror]. Hitherto it has been assessed [for the Dane-geld] at 20 hides [2,400 acres]. There are 5 hides [600 acres] of demesne [the Lord of the Manor’s home farm] with 5 ploughs, in addition 50 villeins [ small farmers paying rent in services on the demesne instead of in money] and 3 cottages have 19 ploughs between them. There are 7 slaves, and enough meadow to feed 4 plough-teams [ 32 oxen] and enough woodland for 100 pigs. In all it is now worth £16, as it, as in King Edward’s [the Confessor’s) time; when received [in 1066] it was worth £11. Queen Eddid [Edith, wife of Edward the Confessor and sister of his successor, Harold] used to hold this manor.’

Claydons drop in value from £16 to £11 is probably to be explained by the destruction caused by William the Conqueror’s army on its circuitous march on London after the Battle of Hastings.

If the agricultural statistics are correct at least three quarters of the parish must have been arable and the woodland (at the southern end of the parish) cannot have been much more extensive than it is to-day. The total population was probably about 360 souls.

Nothing is known of Alric; he was perhaps Queen Edith’s cook and had received Claydon as a reward for his culinary services. Edith was a keen church builder and Claydon Church may have been erected at her expense. There was certainly a church in Claydon in 1129, and as the village is referred to as Stepelclaendon about 1218 a steeple or tower must have been in existence by that date. Nothing, however is left of the old church. The chancel, the oldest part of the present church, dates from about 1380.

After Alric ‘s death the manor reverted to the King, and Henry I gave it to Edith Forn, a former mistress of his, on her marriage to a Norman nobleman called Robert Doily. Later Edith and Robert founded Oseney Abbey in Oxford, which they endowed with several churches, including Claydon’s. This meant that the Bishop of Oseney became the Rector of Claydon and received the tithes due from the parish.

On Robert’s death Edith presented Oseney Abbey with 4 hides of land in Claydon, and her grandson Henry (who was Henry II ‘s Constable) and other benefactors later made further grants of land in Claydon to the Abbey, all of which came to be known as the Rectory Manor and remained in the hands of Oseney Abbey until its dissolution by Henry VIII.

The relevant documents, some forty charters dating from about 1150 to 1281, have now been printed by the Oxford Historical Society and incidentally these Oseney Charters provide a good deal of information about the early history of Claydon. Thus we learn that all legal transactions at that time took place in St Michael’s Church in the presence of the whole parish.

We hear of a watermill in possession of the Doilys, and a windmill (which must have been one of the earliest in England) and a decoy belonging to Oseney Abbey. The farmers’ land was in half-acre strips which were scattered higgledy piggledy over the two large fields into which the parish was divided. Many of the place names and field- names mentioned in the charters still survived (or did until recently).

Thus Kingsbridge (possibly from the king’s highway which passed over it), Redland (reedland), Bean Croft, Elder Stump, Little Marsh, Long Lands, Portal, Small Thorn Furlong and Whitfield are all names with a continuous history in the parish from the thirteenth century.

Claydon Brook was then called the Burn (later corrupted to Bune and Bone) and the stream From Twyford was always the Brook. Further glimpses into the life of medieval Claydon are afforded by the Hundred Rolls of 1278. The population had increased by then to some four hundred souls.

This included five freemen, each farming from thirty to two hundred acres, and thirty-two villeins with thirty acres each (for which they paid in money or services 7s. a year). There we’re also thirty-two cottagers with smaller holdings. The entire names are given in full. The surnames were clearly mainly descriptive, either professionally (there are two Smiths, a Butcher, a Tailor, a Miller, a Woodward, a Gardener and a Fowler) or geographically ( e.g. Richard Scot, Walter of Ireland, Stephen of Cornwall, Thomas Horwood).

The Oseney also include references to Richard the Gascon, Robert Sent, William of Whitchurch, Thomas of Hampton (Northampton probably) and Walter of Twyford.

Medieval Claydon was thus, a good deal more cosmopolitan than one might have expected. For the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries there is less to record.

The principal manor passed from the Doylys to a John Fitz Geoffrey, who may or may not have been the John Fitz Geoffrey who in 1242 fell from a cart into the Burn and was drowned, by 1300 the manor was in the possession of the Earl of Ulster, from whose family it passed by marriage to Lionel Duke of Clarence (Edward Ill’s second son), and eventually to Edward IV and Richard III. granted the manor for life to his widowed mother, Cecilia Duchess of York, and after her death Henry VII gave it first to Queen Elizabeth (Edward IV’s widow) and then to Katherine of Arragon. Few of these grandees are likely to have visited Claydon.

The demesnes of both the Claydon manors were normally let and Claydon must have been generally free to manage its own affairs. Some degree of prosperity and in dependence is proved by the fact that in the fifteenth century the village built for its own use a ‘ common house ‘ fifty-six feet long by eighteen feet wide.

This apparent precursor of the modern village hall may have been identical with the Church House (to which there are several references in the seventeenth century and which was still in use in 1833), which was an almshouse maintained by the parish for the deserving poor.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post